Heavy Tails and Altruism: When Your Intuition Fails You

What do black swans, investing, and altruism have in common? Heavy tails. We don’t see them often, but when we do, they change lives.

Heavy tail is a concept from statistics but as we will see, it has some very tangible consequences for our lives and decisions. It describes events that tend to escape our experiences but rule them anyway. We don’t see them every day, but you can find them in startup investing, charities, gold mining, or pandemics. Can you spot them and adapt?

The post is divided into three parts: starting with what they are, followed by thoughts on how they matter for our decision, and concluding with some concrete life advice with a special focus on altruism.

What are heavy tails

Ron was, like most men in his Alaskan village, a fisherman. Every day, he would go to his spot to catch salmon. Sometimes the catch was bigger, sometimes smaller, but overall he was doing as well as anyone else. Then he heard about the discovery of gold in Alaska, and so he and other villagers tried their luck. Each picked their spot and started mining. One or two got rich beyond dreams. They found enough to buy several establishments and make further profit. The rest of them found almost nothing. Ron thought: there must be enough gold for all of us, I just need to work harder, like I did when the catch was poor. But nothing changed. He and most of his friends were doing much worse than they did in their village and, eventually, they all returned back to fishing.

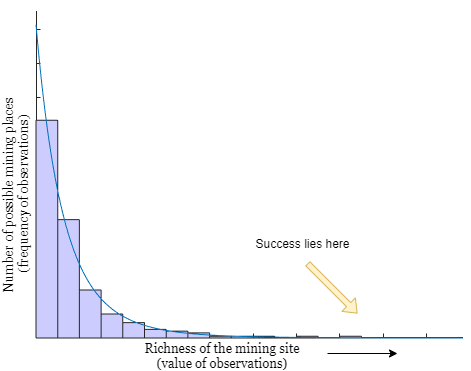

A similar story could be told nowadays if we substitute an ordinary day job and venture investing, for instance. Why are they so different? If you pick a random salmon from the ocean, there is variance in size but you never catch a salmon 100x bigger than the usual. It’s an entirely different situation when picking a spot for gold mining because the distribution is very different. While there might be plenty of gold in Alaska on average, they are concentrated in few rich deposits. If we were to divide mining places to buckets by how rich they are and plot the number of places in each bucket, we would get something like this (disclaimer: I’m not a gold prospector):

There are very few places with a very high reward in the right part— the tail! And they make all the difference. This is the essence of heavy tails in general: Some observed values (e.g. gold deposit size) are much larger (impactful) than others but increasingly rare. However, they are still frequent enough to have a huge impact on the average.

Ron’s mistake was he didn’t think about this and didn’t adapt his strategy compared to what he was used to. As we’ll see later, heavy tails can have a huge influence on our decision making in certain fields, including altruism.

This is the essence of heavy tails: Some observations are much larger than others but increasingly rare. They are still frequent enough, however, to have a huge impact on the average.

Terminological side-note

Before I continue, let’s get two things out of the way:

- I’ll be rather informal. Stay tuned for a future blog post about all the exciting details about heavy-tailed probability distributions (e.g., why they repeatedly pop up in nature and society).

- You may have also heard about fat tails or long tails. For all practical purposes in this post, they are the same thing as heavy tails. Power law, Pareto, and log-normal distributions are also related.

Key characteristics

A key characteristic of a heavy-tailed distribution is that frequent observations are accompanied by rare observations that “tail off”. They are not rare enough, however, not to contribute significantly to the mean of observations; quite the opposite, the rare observations do affect the mean disproportionately. This is unlike the normal distribution (bell curve), where most observations are quite close to the mean and large enough values do not contribute to the expected value because of their negligible likelihood (like giant salmon!).

Here’s another example: Imagine you are an alien and your boss wants a report on average human features. So you abduct a hundred random people and try to draw conclusions:

- For height, you measure the heights of all people and calculate the mean. What you get is an imprecise, but still pretty good estimate of how tall an average human is and how much heights are spread from the average.

- For wealth, you question the hundred people about their net worth. How much you learn about humanity? Not much. Whether Jeff Bezos is or is not among the abducted makes a lot of difference.

While heights follow a normal distribution, wealth follows a heavy-tailed distribution. A random sample from the latter consists mostly of small values. The median is significantly less than the average.

How to adapt to heavy tails

The problem with observations or events from a heavy tail is that even though they are frequent enough to make a difference, they are rare enough to make us underestimate them in our experience and intuitions. Let’s look into their properties in more detail and contrast them with what we are more used to.

Even if significant events from the heavy tail are relatively rare, they can matter more than all the small ones combined. This, in turn, can have a huge influence on our decision-making.

Cost of exploration

The example above about measuring wealth demonstrates how heavy tails make understanding the average or finding outliers difficult. Just like Ron didn’t do well picking up a single mining spot at random, a venture investor looking for the next Instagram cannot pick a startup at random. The cost of blind exploration is just too high. Most startups will gain you significantly less than the average return.

That doesn’t mean all is lost. You just need to try many options and, ideally, have some sort of compass that leads you towards the tail. Inspecting many startups and having a deep understanding of how business works will make you much more likely to find a cash cow.

It also doesn’t mean that exploration isn’t useful if you don’t have the compass yet. The career advice website 80,000 Hours, for instance, recommends exploration early in your career precisely because it helps you gain the missing information and understanding about the best career paths for you.

Finding large outliers really matters

While exploration can be more costly, it can also be more rewarding. When choosing a car, spending more time on the choice isn’t likely to give a ten times better result. On the other hand, the impact of charities can differ by orders of magnitude (as we’ll see later), and devoting more time to the right choice does make a lot of difference.

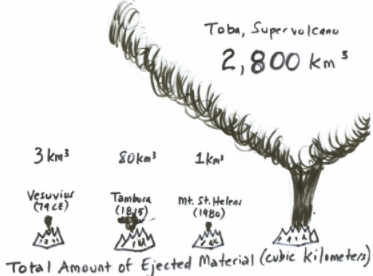

Conversely, if an outcome can be not only positive but also negative, a failure can wipe all of the previous successes. A single pandemic can kill more people than all previous ones combined. All your capital gains over many years can be wiped out by a single market crash. Many other catastrophic events such as earthquakes or wars have a heavy tail.

Knowing this, one can recognize the importance of limiting losses ahead and be more cautious with experimenting. This is also one of the reasons why working on the prevention of catastrophic risks can be more important than our intuitions tell us.

Rare events are hard to predict

We are all subjects to biases and tend to overestimate the confidence of our predictions. While this is not specific to heavy tails, we should be even more cautious with them. Our intuition is trained from feedback and experience, but rare events don’t give us many learning opportunities. Sometimes it is fundamentally difficult to get enough data for a prediction. This doesn’t mean there is no point in predicting, we just need to acknowledge the uncertainty.

Tail events are rare enough to make us underestimate them in our intuitions.

Take a moment to let these findings sink in. What decisions in your life can lead to ten times the difference or more? Which don’t? When do you need to try many options before you know what’s possible? What might you be underestimating?

Lessons for life and altruism

Heavy tails can sometimes be found in places where we have many options but where only a small fraction is substantially better than others. Here are some practical examples.

Lesson 1: Be deliberate in your altruism

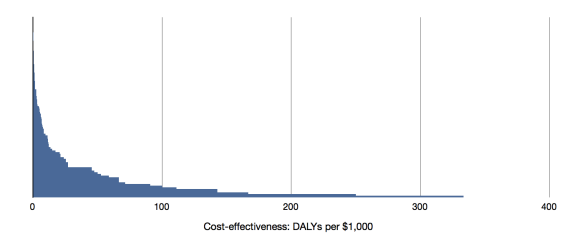

If you have ever donated to a charity, think about where that money went for a moment. If the impact of charities followed a heavy-tailed distribution, it would mean a couple of things.

First, finding the top charities or interventions would make a tremendous difference. This, in turn, means that the effort that goes into discovering the best interventions is very valuable. Compare this to the traditional way we donate — based on who approaches us on the street or what problem we feel a personal attachment to.

Second, established charitable organizations often offer a wide variety of programs they fund. If we don’t know any better, this looks like a good idea — it’s like a wide investment portfolio: there is less risk of neglecting a cause and everybody can choose their favorite. But understanding heavy tails tells us that charities with few highly effective projects will do better than those with many projects of unknown impact —the vast majority of randomly chosen projects will have effectiveness below average. (That’s not to say they choose randomly, but measuring impact is really hard and as a result often neglected).

Finding the top causes or charities or interventions would make a tremendous difference. But does charity impact have a heavy tail and can we tell what it is at all?

You may be thinking: this is nice in theory, but does it apply to the real world? Does charity impact have a heavy tail and can we tell what the impact is at all? The best data we have is on health interventions, where analysis by the DCP Project shows their cost-effectiveness does follow a heavy-tailed distribution indeed. There is other evidence that some interventions within a program area are often more than ten times as effective as others, even when excluding entirely ineffective programs. And different program areas themselves can have huge differences in their importance.

So not only how well I do, but what I set out to do in the first place makes difference? Fishing or gold mining? It seems so — according to 80,000 Hours, to pick the right cause area is the most important thing, while picking the right intervention can give you an additional 2–3x boost.

If you don’t want to miss on opportunities, a good starting point is the research by 80,00 Hours on the most pressing problems or advice on effective charities from GiveWell.

Lesson 2: Know when to trust your experience and when to trust experts

We talked about how we cannot trust our experience in situations where the risks have a heavy tail. The COVID-19 pandemic is a great example of an event eclipsing any other experience we’ve had about infections in our lifetime. Comparison to something familiar, like the flu, does not quite capture the overall impact it has had.

The lesson here is: learn when to trust your experience and when to trust experts. It’s not one or the other, it all depends on the context.

Here is one rule of thumb: In areas where things are almost never 100x better or worse than most, you can probably learn from experience. Otherwise, the heavy tails may rule and field experts (especially with mathematical background) deserve our full trust. If you are choosing a plumber or a dentist, one probably won’t be 100x better than most and you can learn how to spot a good one. But when there are rare 100x better nonprofits, you should not judge the nonprofit sector by what your limited experience has been so far. Nor should you for pandemics.

When there are rare 100x better nonprofits, you should not judge the nonprofit sector by what your limited experience has been so far.

Lesson 3: Know what to expect from hiring

80,000 Hours says there is some evidence the individual job performance does not have a heavy tail even in complex jobs (e.g. a doctor). But the variance is high in the tails for the most difficult and creative work like academic research and this could have implications for hiring.

But that’s just individual job performance. The total impact one has is likely a product of individual performance, the effectiveness of the organization, the importance of the problems one is working on, and other factors. Like cogs that fit together to multiply their speed. This is exactly the kind of situation that gives rise to heavy-tails.

What this means is that you don’t need to be exceptionally talented yourself to have a large impact if you use the right leverage. And it turns out that choosing the right career may be one of the most impactful things you can do in your life.

Conclusion

I owe you one thing — I promised to talk about black swans in the intro. But I was really talking about them the whole time. As the author of The Black Swan said, “fat tails is a technical term for Black Swans”. You can put these two concepts in your mental library next to each other. And there is much more I could add that doesn’t fit in this post, like Peter Thiel’s advice on investing, hits-based giving in philanthropy, or barbell investing strategy.

Heavy tails do not rule all of our choices, but when they do, they can have a significant impact. First, we should learn to spot them — they often hide in places with many options where few are significantly better than the rest, or in places where several independent factors multiply.

Then, we should learn to adapt — know how much is exploration valuable, when you need a compass, and when exploration is dangerous and you need to prepare in advance. Also, learn when to trust your intuition and when to trust experts.

Finally, think about what it means for your life. What decisions have an outsized impact? When do you need to try many options before you settle? There is evidence that choosing your career or altruistic actions, such as where to donate, are such decisions.